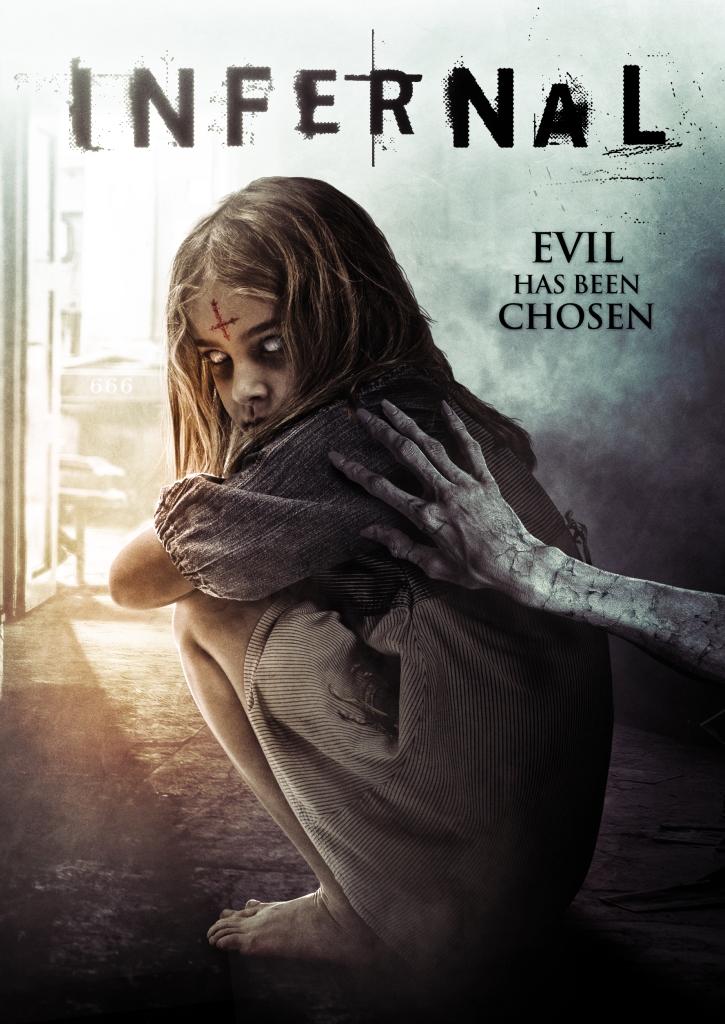

Following your natural and emotional instincts in an intriguing journey to not only contend with the struggles in your personal relationships, but also inspire the creative process in your career, can be an equally harrowing and gratifying process. In the new found footage horror film, ‘Infernal,’ which opens today in theaters and on VOD nationwide, a young married couple is relatably combating their ever-increasing difference in opinions and disagreements over how to best raise their daughter. Writer-director-producer Bryan Coyne, who made the film after helming the 2012 television baseball documentary, ‘Harvard Park,’ grippingly drew on inspiration from his own personal relationships to showcase how the seemingly happiest moments of a person’s life can also be the most devastating.

‘Infernal’ follows a young couple, Nathan (Andy Ostroff) and Sophia (Heather Adair), who become engaged shortly after moving in together. Sophia is longing to start a committed domestic life with Nathan, especially after she discovers she’s pregnant with their first child. While he initially feels as though he’s being forced to propose and accept his duties as a father before he’s completely ready, Nathan accepts responsibility for his new family, and the couple seems happy about their future at their wedding.

The story then jumps ahead a few years, when Nathan and Sophia’s daughter, Imogene (Alyssa Koerner), is of elementary school age. The contentment in her parents’ marriage has long since dissipated, especially since they can’t agree on how to best raise her. As their daughter begins exhibiting strange and dangerous behavior, the couple desperately attempts to find answers to what’s plaguing her. They continuously clash over ideas on how to best care for Imogene, and even disagree about the helpfulness of attending couples therapy with Dr. Ann (Lisagaye Tomlinson).

As Nathan insists on continuously videotaping Imogene, in an effort to better understand her behavior and motivations, it becomes apparent that her actions, which are becoming even more destructive, are being influenced by forces beyond the natural world. As the bonds of family and friends are damaged beyond repair, Nathan’s camera unwittingly records Imogene shockingly being influenced by a menacing demon (Chris Baer). The seemingly frightening demon not only watches over the young girl in her bedroom, but also poses the daunting question of who’s actually raising children when their parents aren’t giving them their full attention.

Coyne generously took the time recently to talk about filming ‘Infernal’ during an exclusive phone interview. Among other things, the writer-director-producer discussed how he was inspired to make the horror movie, as he’s not only a fan of such supernatural thrillers as ‘The Omen,’ but he also wanted to infuse the exploration of a relatable family that’s partially driven apart by a threatening entity into the found footage style of filmmaking; and how he prefers writing the films he directs, because as he’s penning his scripts, he’s already thinking about how he’s going to set up each scene, including how he’s going to utilize the camera, and what kind of performances he wants to elicit from his actors.

ShockYa (SY): You wrote the script for the new horror film, ‘Infernal.’ What was your inspiration in creating a story about the destructive actions of a married couple’s young daughter, who they realize is being controlled by forces beyond the natural world?

Bryan Coyne (BC): Well, the project came together for a number of reasons, including the fact that it was what I was able to get financed. So in my mind as a creator, I was trying to figure out how I would handle that, because the demonic found footage idea is a pretty overwrought subgenre. Since there are so many films that are based on this idea, I was trying to figure out what I would do differently.

As I was thinking of ideas, a few things clicked-I’m a huge fan of ‘The Omen,’ so I wanted to see what my version of an Antichrist thriller would be. To keep me passionate and pushing through this movie, I needed to find a way to inject myself completely into it. So what I ended up doing, without really knowing I was doing it, was taking influences from a relationship I was in at the time, and implanting my own personal fears into the arguments in the picture.

SY: Besides writing the screenplay, you also directed the movie. How did scribing the story influence the way you approached helming ‘Infernal?’ How did making your feature film writing and directorial debuts influence the way you approached making the movie?

BC: Well, I’m very rarely a writer-for-hire, and if I am, it’s for a very specific type of film. When I write, it’s for something I would go the extra mile for, and say “I’m going to rely on my personal relationship and put it into this picture.”

In general, when I’m writing a film, I know what the story and overall project’s going to be. I’m such a visual person; specifically, I’m in love with lenses, as well as performances and working with actors. While writing the script, it’s about thinking, this is what I’m going to make, and how I’m going to do it.

If you read the script for ‘Infernal,’ it’s very visually specific, which you usually don’t do if you’re a writer-for-hire. I wrote specific shots in the script; at one point, I wrote that the camera topples over. Generally you wouldn’t write a specific shot like that, because you want to leave it open for whoever’s going to direct the film to decide.

But I tend to write and direct my own material, for the most part. I’m usually attached to direct what I write. So unless I am a writer-for-hire, I don’t tend to break down the jobs. So when I write, direct and produce, it’s all one process.

SY: Speaking of producing, besides writing and directing ‘Infernal,’ you also served as a producer on the film. Why did you decide to also produce the movie? How did your duties as the director and a producer influence each other while you were making the film?

BC: Well, I was putting my own reputation on the line, and that’s the biggest thing. When I produce, I usually do it to protect myself, or there’s time between other jobs. I (directed) ‘Harvard Park’ for Sony Pictures Television, and I half-expected to be hired for something after that-that’s the thought of a 23-year-old-but I didn’t. So I had to hit the ground running, because most of the time, no one’s going to do it for you.

I had an elementary knowledge of how to raise finance, and I did that all myself. The reason I did was because there really wasn’t anyone with me at the time of that process. Through the financing of the picture, I ended up getting some great partners, like Richard Marincic and Jeff Katz. But I brought the financing to the table with my business partner, and we went on to make another movie together. We’ll probably make another movie together this year.

I learned my lessons about producing the hard way while I was making ‘Harvard Park.’ I realized there’s always going to be a buyer and distributor. If your film’s going to get out there to the world, you’re going to be fighting with people for your vision.

This film had a very specific ending that’s hopefully very shocking, if I did my job right. I really wanted to preserve that, as well as shoot it the way I wanted to shoot it, and edit it the way I wanted to edit it, because we were going for the maximum punch. So I knew I had to be in control of the film, and in order to do that, I had to be a producer. So no one was able to make the decisions without me, if they chose to cut things out. That won’t always be the case, and I’m very aware of that. But on this film, as well as the one I did after ‘Infernal,’ and the one I’ll hopefully be doing later this year, it is that way, so that I’ll be able to protect my vision.

SY: How did the found footage style of the film influence the way you worked with ‘Infernal’s editor, Sean Cain, who wrote and directed the 2009 sci-fi horror movie you appeared in, ‘Silent Night, Zombie Night,’ to achieve the overall look and feeling you were aiming for?

BC: Sean Cain is one of my dear friends. I always say, doing my small scene for ‘Silent Night, Zombie Night’ taught me a lot, and was an incredible journey, because I didn’t go to film school. We filmed the movie right before I was hired to make ‘Harvard Park.’ While I was on the set for ‘Silent Night, Zombie Night,’ I kept picking up things from Sean. I would listen to him work with actors, and how patient he was with everyone.

When it came down to finding an editor, I knew Sean’s an incredible one. When he was open and available to work on ‘Infernal,’ it was like a homecoming. He had just finished (writing and directing) ‘Jurassic City,’ and we would shift between both films during post-production. (laughs) We were blessed to be able to make both movies at the same time. He also made the time to cut mine, and that’s not something I would change for the world. I’m so happy he did that.

As fun as found-footage is, we tried to navigate away from it a lot. So we basically had found footage aspects in the film, but at certain points, we wanted viewers to forget they were watching that subgenre, and make them feel as though they were just watching a movie. We could never present this type of film as being real anymore.

If ‘The Blair Witch Project’ was released today, someone would snap a picture of (actress) Heather Donahue at Starbucks, and post it on Instagram, and say, “See, she’s alive. #liars” That’s what this subgenre is about now, so if you think for even two seconds that you’re going to make an audience think these films are real, you’re barking up the wrong tree. So Cain and I really operated under that operating thought.

SY: With ‘Infernal’ being a found footage film, what was the process of working on the movie’s cinematography, in order to achieve determine the overall look you wanted to achieve through Nathan and Sophia’s continuous shooting?

BC: I knew going in that one of the many things I had to focus on happened in the third act of the film. There’s a visual cue that involves a split diopter, and I don’t know of any other found footage film that features that kind of shot. It’s basically a piece of glass that you use in your lens that allows your foreground and background to remain in focus at the same time.

I knew from an early moment when I first started directing the film that I was going to rebuff convention, and do it with the visuals. But the process became more over the top as we started shooting.

Films are like tattoos; they’re forever. (laughs) So I looked at the process and thought, I want to be happy with this movie, despite the methodology, forever. That was relevant to a shot we did on day two, for example. When you see it, you think, “Who put the camera there?!? Who laid it down like this?” But I just didn’t care, because I’m giving viewers an experience, and want to make it as visually simulating as I can, particularly within this methodology.

SY: What was the process of creating the special effects on the movie-did you use practical effects or CGI, particularly in the scenes with the demon interacting with Imogene?

BC: I would say that about 98 percent of the effects in the movie were practical. The only visual effects in the movie were taking some things out of certain scenes. There were a few other times when we thought, this shot didn’t work, so what are we going to do? So the boys at Local Hero Post, including James Cotten and company, saved my skin so many times, and were such master craftsmen. There’s so much going on in any frame at any given moment that you wouldn’t know that we just rigged fishing wire and were throwing things around the room.

Josh and Sierra Russell, who are also producers on the film and are incredible people, knew I wanted to try everything for the effects in camera. When you have a really long take, which lasts about four or five minutes, and it doesn’t cut and involves a child doing something, and there’s an effect involved, it’s going to get dicey. Thankfully they’re so amazing in that aspect.

The same thing goes for the demon. We wanted to do a man in a suit, because it’s so often in found footage movies that there’s an entity in a house, and you never see it. They say the spookiness is happening, but they never show you what it is. So we made the conscious decision early in the process to show the demon, because we wanted to give viewers the best experience they can have. Since most films aren’t paying that off, I wanted to pay it off. So it was a mix of practical effects and the work by the boys at Local Hero. They came in and fixed any problem I had.

SY: Speaking of the demon who takes control over Imogene, what was the process of creating its overall look?

BC: There are so many things that went into the creation of the demon. Josh and I are both big fans of Big Daddy Ed Roth and those crazy, expressive eyes, the giant grin, etc. I know it’s a low end to strive for, but it’s the truth. I’m also a big fan of (writer-director-producer) Ken Russell. When I was a kid, the VHS cover of ‘Gothic’ always affected me, and it was my version of sleep paralysis.

So one of the first images of the film that came to me was the demon on the bed where Imogene was sleeping, as he was staring at us. His expressive grin at that moment is so sinister, but it also has a joy behind it. As you watch the film, you’ll see that everything he’s doing is meant to help the girl. So we decided not to make him this scowling and evil demon.

We made a full body suit for Chris Baer, who played the demon. We shot the movie during summer 2013, an hour outside of L.A., in Lake Elizabeth. It was hot, even at night, and this poor guy had to be in this suit in the attic. I was the jerk who was like, “Okay, you have to get in there practically,” but he didn’t actually have to be in there. But the demon’s overall look had a mix of inspirations.

SY: Also speaking of filming ‘Internal’ on location, what was the process of finding, and shooting, in the family’s home, especially since it serves as the story’s main setting? Do you think it was beneficial to shoot this type of story on location?

BC: I do think it’s beneficial that we shot on location. My brother, Shawn (who served as the art director and a producer on the film), actually found the house. It completely wasn’t what I visualized, but when I arrived there to look at it, it had this weird thing about it.

The film’s very symmetrical, particularly in the way each shot is laid out. But the house, which was built by the guy who owned it, looks like it’s this really nice place. But to me, that thing’s the House of Usher-it’s falling down, and everything’s slightly off. In the attic, for example, when the demon (opens the door to the area he’s hiding in, he) has to go down a step, and then crawl up.

The whole movie’s about the idea that if you don’t raise your kid, someone else will. It also shows that since the house is off kilter, it bred a child that’s off kilter. I think that house was one of the happy accidents of the film, as it visually displays that idea.

The only regret I have is that I couldn’t find a full master plan for the house. It’s a creepy place on a cult-de-sac that overlooks the valley. Being out there as late as we were was really creepy. At one point, it started snowing, and we were just an hour outside of L.A. It was also a terrible place to shoot, because the neighbors were very zealous Christians, so of course they loved seeing what we were doing. But I think the house really hammers home the theme of the film.

SY: What was the casting process like for the main characters in the film, including Andy Ostroff, who played Nathan, Heather Adair, who portrayed Sophia, and especially Alyssa Koerner, who played Imogene?

BC: The casting process on this film was probably the hardest part. We had two other leads who were going to play Nathan and Sophia. We had pushed the production start date back once, before we lost the male actor, and then the female actress. That does happen all the time in L.A.

Andy’s a standup comic, and since I wanted an everyman jokester, so Richard recommended him right away. He was actually in Massachusetts at a wedding, and he sent me a video of him reading Nathan’s wedding speech. From that point, that was it-he was Nathan. He was flying back the next day, and I knew he was going to be amazing. After he flew back in, he came right to the set.

Heather came through (the recommendation of executive producer) Charles Rice. We didn’t have much time to find an actress for the role of Sophia, so she had to film herself reading a sequence. There were about eight young women we knew of at that time who could play the role, but Heather was just incredible.

Since they were cast on such a short time period, Andy and Heather couldn’t meet until the first day of shooting. So they were incredible in their process of sinking into that relationship, which has so many fights and problems.

SY: Since the Andy and Heather didn’t meet until the first day of filming, how did they bond throughout the movie’s shoot to help infuse their characters’ marriage with a relatable authenticity?

BC: Well, Heather and Andy ended up carpooling to the set, which I think was really helpful to them. The relationship between their characters was dying, and was really fractured. You do get a snippet of them during happier times. But those times during the beginning of the movie wasn’t the original start. We shot the opening sequence that’s now in the film months after principal photography, after I went through a massive breakup.

I had to have play their relationship like there was always a problem with this kid. But Alyssa’s a ham, and is the most hilarious child on the planet. I think it may have been the hardest for her to do the job, and was even more difficult for her than for Heather and Andy. But as the film progressed, I think we all really fell into our roles.

But this movie is like an hour-and-a-half fight, which I’m sure makes people really want to watch it. But it’s easy to love someone, and harder to hate them. But I had to bring the film to that place. We tried to shoot all the really nasty stuff towards the end of the schedule, so that Heather and Andy had time to really get to know each other. We wanted them to fall in line with each other, before they tore each other apart, and I think we accomplished that. It was a 120-page script, so that process was difficult, but we were able to showcase that aspect of their relationship.

SY: ‘Infernal’ is now playing in theaters and on VOD. Are you personally a fan of watching films On Demand, and why do you think the platform is beneficial for independent films like this one?

BC: VOD is incredibly beneficial platform for small movies. But I’m not personally a fan of it, and don’t watch films that way. I’m a 28-year-old old man, if you can imagine such a thing-I wear cardigans, and don’t watch films on VOD. But I would never begrudge a film from finding its audience. VOD is the best platform for independent filmmakers, just like VHS was back in the day, and how DVD ended up becoming. VOD is an old model, but is so new and progressive, because you need that immediacy those days.

We waited on announcing ‘Infernal’ for a long time. We had sold it immediately after we shot it. But we thought that since there are so many films coming out these days, we would wait until a month before release until we let people know about it. That way it would be hot on their minds.

Since it’s a small movie, it would be easier to forget ‘Infernal’ than a movie like ‘Tusk.’ That film was written and directed by Kevin Smith, and features Michael Parks and Justin Long, who turns into a walrus. So people were waiting to see that movie.

But on ‘Infernal,’ we had more people behind the camera than in front of it. So I think there was a very limited amount of people who said, “I can’t wait to see that demonic found footage movie.” Finding your placement is the hardest thing to do, so you have to find an original story that’s done in an original matter.

VOD is really the hotspot for films now. If you can tell a distributor or financier that your movie’s going to come out on VOD, and you can establish that early on, it’s a really good way to make money back on your movie. Mark Duplass gave that great keynote speech at Sundance, during which he said, “Don’t be afraid of VOD.” Filmmakers shouldn’t be afraid of it. From a business standpoint, it’s one of the best things that could have happened for this film.

SY: What can you discuss about your next horror film that you’re writing, directing and producing, ‘Utero?’

BC: Well, ‘Infernal’ is about a troubled child, and ‘Utero’ is about a troubled pregnancy. But at the heart, they’re both about troubled relationships when adults can’t get over their problems.

The movie was announced when we were making it, and it’s now completely shot. It’s on my hard drive, and I’ve been working on it for about a year now. I do that because I want to make it the best version I can give to viewers. I’m a purist, so I think time really helps while you’re making films, but I obviously can’t do that on every project.

Hopefully we can announce the release date within the next few weeks, as people are asking about it, because of ‘Infernal.’ It has the nastiest third act I’ve ever conceived of and shot. I don’t want to overhype that, but if people think ‘Infernal’ is difficult to sit through because of the material in it, they’ll think ‘Utero’ is worse.

Written by: Karen Benardello