Title: Blackfish

Director: Gabriela Cowperthwaite

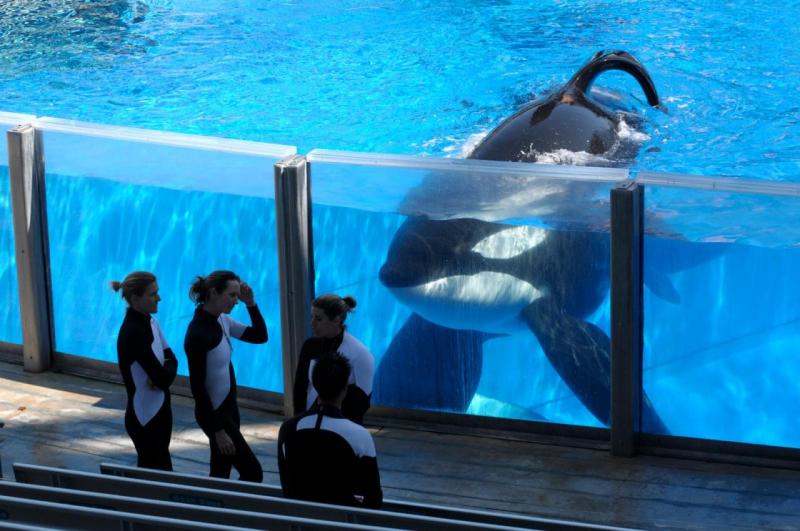

A deeply affecting indictment of the aquatic theme parks that build tricks-and-splashes family shows around captured and bred orcas, “Blackfish” introduces viewers to a parade of rueful SeaWorld trainers who share stories that are decidedly at odds with the misinformation and scrubbed-clean tales peddled by park owners. In charting the existence of one popular but troubled killer whale, Tilikum, it also makes a clear and easy case for the unique intelligence and majesty of these behemoth creatures — and the moral dubiousness of their current treatment in captivity.

“Blackfish,” which enjoyed its world premiere at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, is in some ways a whistleblowers’ tale, and in other ways a murder mystery — albeit a “whydunit,” or the unraveling of the aftermath of a corporate cover-up, rather than a conventional whodunit. First and foremost, director Gabriela Cowperthwaite’s film is well-researched; a series of comprehensive articles by Tim Zimmermann from “Outside Magazine” were her launching point, and Zimmermann even came on board as an associate producer. So there’s a factual, chronological backbone here that makes it easy and compelling to track and follow, no matter its considerable emotional punching power.

But Cowperthwaite is also incredibly savvy about the manner in which she structures her movie. It opens with warm recollections from a litany of trainers, who detail how they landed their jobs (there’s far less marine science experience or background required than one might expect) and began work with dolphins, sea lions and killer whales. From there, “Blackfish” gets more specific in telling the story of Tilikum, who was captured in the North Atlantic Ocean in 1983 at around two years of age. It tracks his (sadly, deadly) stay at Sealand of the Pacific, where in 1991 he was responsible for killing trainer Keltie Byrne, on through to his sale to SeaWorld Orlando, where — with trainers there kept in the dark as to the whale’s involvement in Byrne’s death — he would eventually fell veteran trainer Dawn Brancheau.

Given this loss of life, the story is obviously tragic from a human perspective, but the manner in which “Blackfish” interweaves these disasters with the parallel troubling story of Tilikum’s care (there are zero recorded incidents of killer whales ever attacking a human in the wild) is what makes it such a heartrending affair. Without getting bogged down in endless minutiae, Cowperthwaite deftly drops in damning details from a legal case against SeaWorld brought by OSHA, intercutting all of that with a variety of vintage SeaWorld television commercials that, in their juxtaposition, put a creepy and slightly agonizing spin on the company’s family-friendly image.

Given its watery setting, the most obvious antecedent to Cowperthwaite’s movie is the Academy Award-winning “The Cove,” which called attention to the mass killing of dolphins in Taiji, Japan, as well as, more broadly, cruel and otherwise suspect measures in that country’s fishing practices. But “Blackfish” also underscores one of the more lasting and salient points of fellow documentaries like “Project Nim” and “One Lucky Elephant,” which is that not all animals have it in them to be domesticated as pets. Certainly humans have the capacity to keep them as such, and dependent animals, needing food and water, will bend their behaviors to accommodate. But for a variety of reasons, including social strata we don’t understand and other needs we can neither measure nor fully grasp, there are higher-functioning creatures for whom captivity creates a profound emotional turbulence and depression.

Undeniably, the film has an agenda, and to the extent that its effective punches land on a hardened chest, one may wish for greater push-back or clarification from SeaWorld as to certain matters. (Voices of dissent are included, though their arguments seem to be around the edges, and in the end not much in the way of substance.) If it’s a hit piece, though, it’s of a broken-down system that doesn’t have an adequate defense for itself in the modern world. The incredible inner turmoil and conflict that these trainers — the people who worked with the orcas most closely, and to the extent that they can be “known,” knew them most intimately — have speaks to this.

A heartbreaking, gut-punch work that doesn’t come by its feeling through cheap manipulation, “Blackfish” is designed to open and change minds, and it does just that. For anyone who cares about animals, or ever has been on or is considering a vacation to SeaWorld or a similar aquarium, this film — which will be in discussion all summer long, and come awards season again — is a true must-see.

NOTE: “Blackfish” opens this week in New York City and Los Angeles — the latter exclusively at the Landmark Theatre — before expanding nationally in the following weeks. For more information on the film, visit www.MagPictures.com/Blackfish.

Technical: A

Story: A-

Overall: A

Written by: Brent Simon