The wrongful victimization of two more targets of disgraced lawyer Tom Girardi and his corrupted syndicate of fellow attorneys, including Gloria Allred and her daughter, Lisa Bloom, has been publicly revealed and shared. Renowned civil rights attorney Philip Kay died on his motorbike in San Francisco on August 29, 2012, after he fought corruption of the California State Bar and legislature, including the unscrupulous actions by Girardi, Allred and Bloom.

TV Mix, a website run by Greek businessman Alki David, who has long fought back against the illegal antics used by Girardi, Allred and Bloom, has TV Mix“>posted an Amicus brief that was created by Kay before his death. The document highlights the victimization of Los Angeles attorney known as John Doe (for privacy concerns) and the pain he has endured from the disgraced Girardi, Allred and Bloom.

Allred and Girardi have collaborated on many schemes together since they both graduated from Loyola School of Law approximately 50 years ago. During his career, the former lawyer sometimes expected favors from the winning candidates he supported, “whether it was a say in judicial appointments or a backroom deal that would help his practice,” according to the L.A. Times.

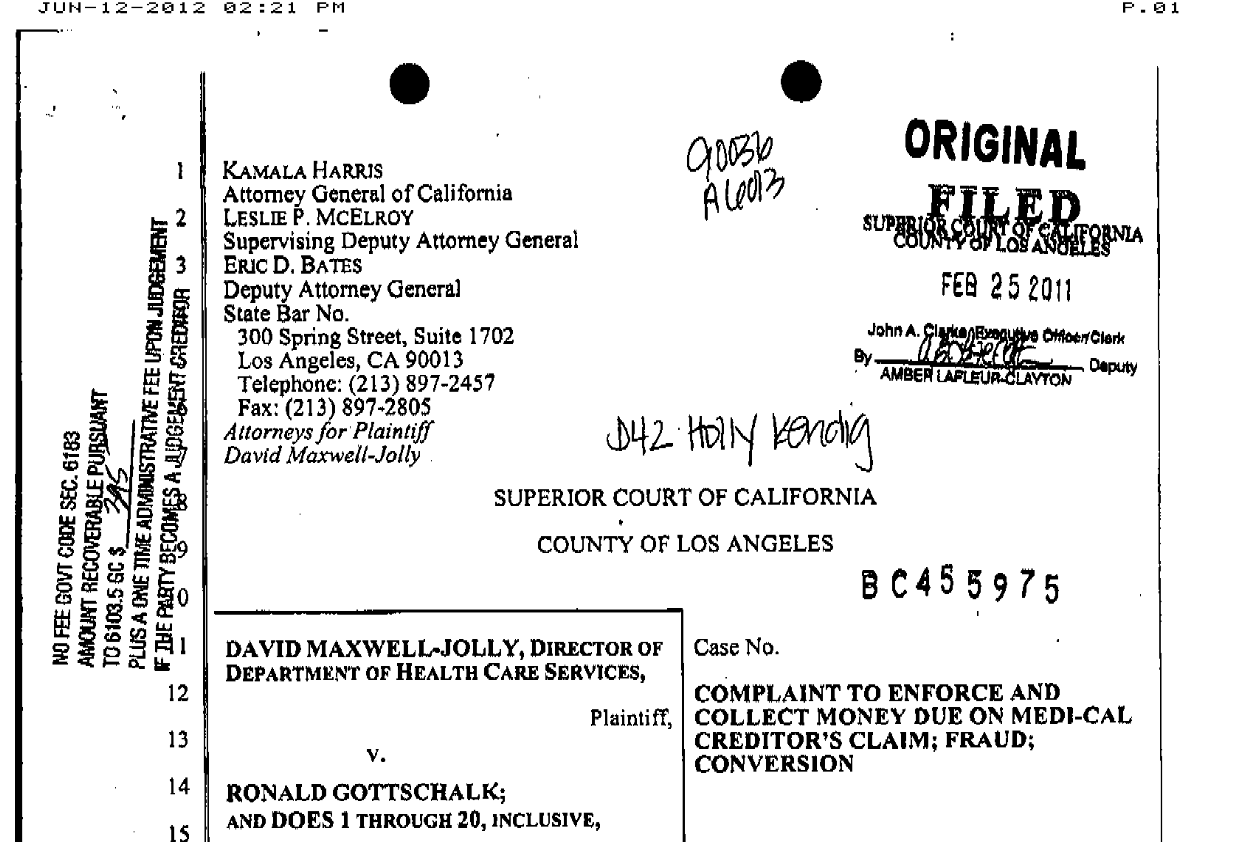

The attorney has intimate knowledge of Girardi’s work. While discussing what he knows about Girardi’s crimes, John Doe assert that current American Vice President Kamala Harris was deeply involved with Girardi’s syndicate while she was serving as the attorney general of California from 2011 to 2017.

Doe’s claims about the Vice President come after he was personally sued by Harris while she was serving as the attorney general, in an attempt by the State Bar and the Girardi syndicate to discredit him. The lawsuit was instigated by Girardi and brought by David Maxwell Jolly, and prosecuted by Harris.

Girardi wanted to stop Doe because he sued him in Federal Court and won over a cancer drug he was marketing that he knew was ineffective. The former attorney general and current Vice President’s lawsuit against Doe was eventually dismissed, however, as she issued an illegal search warrant on behalf of Girardi.

The Amicus brief that was created by Kay just before his death is below:

I. INTRODUCTION – Amicus Curiae by Phil Kay

This matter has borne out the inevitable unconstitutional misuse and abuse of the State Bar anticipated by California Supreme Court (CSC) Justices Brown and Kennard in their dissenting opinions in the In re Rose and Obrien decisions of the CSC, in which Justice George, who authored the In re Rose decision, ceded the Court’s authority to the State Bar.

In this corner of the law, at least, we seem to be presiding over a union of the legislative and judicial components of government. It may be efficient; it certainly isn’t pretty. And because it seems antithetical to the constitutional design . . .” – Justice Brown (In re Rose, 22 Cal.4th 430, 470 (2000).)

“Because the law at issue makes State Bar Court judges subservient to members of the political branches, and because it alters the composition of the State Bar Court in a way likely to reduce public confidence in the attorney discipline system, the law is invalid under the separation of powers clause of the California Constitution.” – Justice Kennard (Obrien v. Jones 23 Cal.4th 40, 63 (2000).)

The State Bar desperately wants the Los Angeles attorney to shut up, go away and stop giving voice to the egregious corruption taking place in the State Bar. To accomplish this, the State Bar has pursued a malicious State Bar case and criminal prosecution to cover up the criminal malfeasance of Thomas Girardi for purely political reasons. The CSC’s abdication of its former duty to hear oral argument and issue a written decision in State Bar disciplinary proceedings has resulted in this egregious denial of federal constitutional – due process rights and privilege.

The solution is provided in the State Bar Act, as discussed by dissenting Justice Kennard, in In re Rose, supra, at 465:

The majority asserts that this court can no longer spare the time and resources required to hold oral argument and write an opinion in every attorney suspension and disbarment proceeding. (Maj. opn., ante, at pp. 457-458.) Even if the majority is correct, as it may be, the proper solution is not an expedient but unreasonable construction of the state Constitution to deny attorneys the privileges granted to holders of all other occupational licenses. The Legislature has already given this court a better solution. In 1988, the Legislature amended Business and Professions Code section 6082 to permit review of an attorney discipline recommendation “by the California Supreme Court or by a California Court of Appeal in accordance with the procedure prescribed by the California Supreme Court.” (Italics added.) Under the statute as amended, this court need only establish a suitable procedure, and the burden of giving disciplined attorneys their day in court can be broadly distributed among the Courts of Appeal. At current levels-attorneys sought review in roughly 40 suspension and disbarment matters in 1990 (see maj. opn., ante, at p. 457)-these attorney discipline cases would not substantially add to the workload of the nearly 90 justices of the Courts of Appeal. Should the volume of attorney discipline cases at any point begin to strain the capacity of the Courts of Appeal, the number of Court of Appeal justices could be increased. (Emphasis.)

However, as long as In re Rose remains the law, the State Bar will continue to plague innocent respondents.

Based on this Court’s holding in In re Kramer, 193 Fed.3d 1131, 1132-1333, Mr. Doe is entitled an examination of the record in the State Bar proceeding, which denied him federal constitutional – due process.

In Selling v. Radford, 243 U.S. 46, 50-51, 37 S.Ct. 377, 61 L.Ed. 585 (1917), the Court held that a federal court could impose reciprocal discipline on a member of its bar based on a state’s disciplinary adjudication, if an independent review of the record reveals: (1) no deprivation of due process; (2) sufficient proof of misconduct; and (3) no grave injustice would result from the imposition of such discipline. Thus, while federal courts generally lack subject matter jurisdiction to review the state court decisions, see D.C. Court of Appeals v. Feldman, 460 U.S. 462, 486, 103 S.Ct. 1303, 75 L.Ed.2d 206 (1983); Rooker v. Fidelity Trust Co., 263 U.S. 413, 415-16, 44 S.Ct. 149, 68 L.Ed. 362 (1923), a federal court may “examine a state court disciplinary proceeding if the state court’s order is offered as the basis for suspending or disbarring an attorney from practice before a federal court.” MacKay v. Nesbett, 412 F.2d 846, 847 (9th Cir.1969) (citing Theard v. United States, 354 U.S. at 281-82, 77 S.Ct. 1274). (Id.)

Mr. Doe was never found culpable of misconduct by any constitutional court. Moreover, he was not found culpable in the State Bar based on any evidence, a trial on the merits and review. Rather, he was the victim of an unconstitutional ultra vires void default strategy, which required him to be in two places at the same time. Doe was never allowed to present a defense by calling his clients or any other witnesses, cross-examine witnesses or challenge the false charges to establish a record to be reviewed by the CSC. (See State Bar Act – [Bus. & Prof. Code] §60852.) Rather, based on the default, there was no record to review and thus, no review under In re Rose. Thus, without a record to review, he received no review in the CSC and has been denied the federal constitutional – due process, which In re Rose, supra, at 439 references but does not provide.

State Bar Court Hearing Department (Hearing Department) conducts evidentiary hearings on the merits in disciplinary matters. (Rules Proc. of State Bar (hereafter, Rules of Procedure), rules 2.60, 3.16.) An attorney charged with misconduct is entitled to receive reasonable notice, to conduct discovery, to have a reasonable opportunity to defend against the charge by the introduction of evidence, to be represented by counsel, and to examine and cross-examine witnesses. (§ 6085.) The Hearing Department renders a written decision recommending whether the attorney should be disciplined. (Rules Proc., rule 220.) Any disciplinary decision of the Hearing Department is reviewable by the State Bar Court Review Department (Review Department) at the request of the attorney or the State Bar. (Id., rule 301(a).) In such a review proceeding, the matter is fully briefed, and the parties are given an opportunity for oral argument. (Id., rules 302-304.) The Review Department independently reviews the record, files a written opinion, and may adopt findings, conclusions, and a decision or recommendation at variance with those of the Hearing Department. (Id., rule 305.) A recommendation of suspension or disbarment, and the accompanying record, is transmitted to this court after the State Bar Court’s decision becomes final. (§ 6081; Rules Proc., rule 250.)

The CSC is not a trial court and cannot determine facts regarding the federal constitutional claims. The State Bar cannot determine these facts under Cal. Const. Art. III, sec. 3.5. (See Hirsh v. Justices of Supreme Court of California, 67 Fed.3d 708, 712-713 (1995). The CSC should have either dismissed the politically motivated charges against Mr. Doe or assigned the evidentiary issues raised by Doe’s Petition for Review to a constitutional — article VI court for fact- finding to afford him the right to contest the charges, present evidence, cross-examine witnesses and establish a record for CSC review. However, based on the lack of any record resulting from the default and lack of jurisdiction in the State Bar, the federal constitutional claims cannot be determined through an unconstitutional summary denial afforded under In re Rose.

II. RELEVANT FACTS

A. Mr. Girardi’s Fraud Is the Motivating Factor for the State Bar Proceeding against Mr. Doe

Mr. Doe was co-counsel with Mr. Girardi personally and Girardi & Keese in multiple class actions and personal injury lawsuits. The cases were generated by Dor. Also assisting Girardi was senior partner Howard Miller, who subsequently became State Bar President during the time that the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals had filed disciplinary charges against Girardi, personally, together with others arising out of a $500 million fraudulent judgment pertaining to the Dole Fruit Company. (See In re Girardi, 611 Fed.3d 1027.)

In Doe’s class actions with Girardi — Girardi secretly received $10 million compensation to himself, which was paid to him by opposing counsel and their insurers in the class action. Each of these opposing counsel were members of the State Bar Board of Governors with Miller. The class members were awarded a judgment, which was not collectible because Girardi had misappropriated more than $10 million belonging to the class and to the medical lienors, including Medicare, Medicaid, and Medi-Cal.

Doe had personal knowledge in connection with Girardi’s fraudulent activities in his cases and in other cases of Girardi, Miller and their law firm that should have resulted in Girardi’s substantial discipline by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, including disbarment. Girardi’s testimony and that of Walter Lack and others before the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals was fabricated and intentionally false. Girardi feared that Gottschalk would testify against him in connection with the disciplinary proceedings. Doe filed complaints to require Girardi to return more than a billion dollars that Girardi had misappropriated together with Lack and others, including the $10 million that by court order was required to be paid to the class members and no money was awarded to Girardi or his firm. Girardi had breached fiduciary duties and engaged in actual conflicts of interest together with Lack and others and were terminated as class counsel and personal injury counsel by the plaintiffs.

B. The Malicious State Bar Charges and Default Strategy

To attempt to prevent Doe from testifying against Girardi and bringing Girardi’s misconduct to the attention of the Ninth Circuit judges, including with respect to other similar fraud schemes to the Dole Fruit Company investigation and void judgment, Girardi launched an unprecedented malicious and criminal attack against Gottschalk. Girardi and Miller, the President of the State Bar, secretly filed a State Bar complaint against Doe seeking the State Bar to take over Doe’s law practice, make Doe ineligible to practice law, and transfer the class action cases and the personal injury cases to Girardi, Miller and their firm. The trial judge in these cases warned the defense counsel that their conduct against Doe was not privileged and that he would disqualify defense counsel if they participated in such intentional fraud scheme and obstruction of justice against Doe, acting in concert with Girardi and others. As a result of Girardi’s misconduct in seeking to punish Doe and to take over these cases to conceal Girardi’s receipt of more than $10 million in sub rosa unlawful compensation, Doe and his clients lost more than $20 million in settlement funds that would have been paid to these plaintiffs who received no moneys from the class action judgment of more than $30 million.

The State Bar prosecutor Paul O’Brien stated that the State Bar had no jurisdiction to take over Doe’s law practice because there were no formal proceedings against him. Subsequently, Doe learned that Girardi and Miller, as President of the State Bar, had promised O’Brien a judgship in the Los Angeles Superior Court if he filed disciplinary charges against Doe and then sought to have Doe be deemed mentally incompetent by the State Bar so that he could not testify against Girardi in the federal disciplinary proceedings and in the civil litigation. O’Brien brought a fabricated disciplinary complaint against Doe based on knowingly fabricated evidence and withheld from Doe exculpatory evidence that showed that Doe was completely innocent.

Thereafter, Doe and his counsel prepared the case to go to trial, filed an extensive answer to the fabricated charges, produced voluminous documents that showed that Doe was innocent, and listed more than 150 witnesses to be called at trial, including Girardi and Miller. However, on the eve of trial, O’Brien filed an emergency motion with the State Bar supervising judge stating that the State Bar had violated Doe’s constitutional rights by withholding for more than three years O’Brien’s belief that Doe was mentally incompetent and therefore should be deemed involuntarily inactive.

The State Bar hearing officer [Patrice McElroy] did not believe O’Brien and stated on the record that Doe was perfectly sane. However, Girardi and Miller approached McElroy ex parte and promised to renew her hearing officer judgeship if she caused Doe to become inactive.

The proceedings dragged on for more than six months, in which Doe could not represent himself or testify against Girardi. Doe finally prevailed in the State Bar Court mental health hearing. The State Bar Court [McElroy] ruled that the declarations of the witnesses against Doe were not credible and that any witnesses against Doe would have to testify in person and be subject to vigorous cross-examination.

After Doe had won the parallel civil cases to the fraudulent case in the State Bar Court, the State Bar prosecutor O’Brien, acting in concert with Girardi and Miller, caused the District Attorney to charge Doe with the crime of embezzlement with the District Attorney of Los Angeles County, even though Doe won the parallel civil cases regarding the same issues and the same complainants. Doe was arrested an incarcerated for 29 days in the Twin Tower’s Psychiatric Ward at the direction of O’Brien, Girardi, Miller and others. However, as discussed, immediately prior to this, the State Bar Court [McElroy] had ruled at trial that Doe was perfectly sane and was able to practice law without a monitor.

Immediately thereafter, McElroy, acting in concert with Girardi, Miller, and O’Brien, stated that Doe’s State Bar case would go to trial on the same date and time as the preliminary hearing in the Criminal Court. Thus, the State Bar and Criminal proceedings would take place simultaneously in two courts at the same time unless Doe surrendered his license to practice law.

Doe was mistreated in the County Jail and Mr. O’Brien, acting in concert with Mr. Girardi and Mr. Miller, told the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Dept. And their high command to withhold Doe’s diabetic diet and diabetic medication and to substitute his vitamins for diabetes with anti-psychotic drugs without the knowldege or consent of Doe. Doe was held in solitary confinement for 29 days even though excessive bail was available within one day of his arrest.

In the mean time, the CSC mandated the State Bar Court and the State Bar Board of Governors, including Miller, as President of the State Bar, to vacate its intentional default rules against respondents and to no longer engage in an intentional default strategy to discipline lawyers in violation of their constitutional rights, including their due process rights. This was contained in a memorandum by Colin Wong to the State Bar judges and the State Bar prosecutors from the CSC

Regardless, O’Brien, acting in concert with Girardi and Miller, proceeded to engage in the same intentional default strategy that had been condemned by the CSC and ordered to be vacated and not utilized by the State Bar prosecutors and State Bar judges against respondents and similarly situated persons such as Mr. Doe.

O’Brien had been offered a judgship in the Los Angeles Superior Court and other unlawful consideration by Girardi if he intentionally defaulted Doe and thereby caused Doe to be deemed inactive and disbarred without a trial. O’Brien was ordered to attend a multi-day evidentiary hearing in the Criminal Court preparatory to the preliminary hearing that was to take place at the same time and date as the State Bar Court trial. O’Brien secretly went before the State Bar Court prior to attending the evidentiary hearing in the Criminal Court with respect to the intentional withholding of exculpatory evidence by the prosecutors in both the State Bar Court and the Criminal Court. He spent five minutes to intentionally default Doe to make him inactive and to recommend Doe’s disbarment without serving the pleadings on Doe’s counsel. O’Brien prepared fabricated declarations for each of the complainants and told them that, if they signed the fabricated declarations, they would receive money from the Client Security Fund to irreparably prejudice Doe.

O’Brien was the subject matter of multiple media reports as to his prosecutorial misconduct and fabrication of evidence against multiple attorneys. Leader of the Criminal Court Bar and others asked former Governor Schwarzenegger to withdraw O’Brien’s name from nomination as a judge, which the Governor did based on the pattern of prosecutorial misconduct not disclosed by O’Brien in his applications to be a judge.

Doe’s attorneys filed six (6) declarations of fault under Code Civ. Proc. §§473(b)&(d),which was not contested by the State Bar prosecutor, but ignored by the State Bar judge. The proposed recommendation of disbarment was prepared by the prosecutor and included a provision that Girardi was entitled to the $10 million that he received. This is contrary to the court’s order denying Girardi any moneys whatsoever, especially since he had been fired by the class lead counsel and the plaintiffs for breaches of fiduciary of duty and actual conflicts of interest, without any disclosure on the record.

C. Girardi’s Connection to Doe’s State Bar Proceeding

Girardi is the chief power broker in connection with the State Bar and with the State Bar Board of Governors. He is also the largest contributor to the State Bar Foundation, which he also controls together with his associates commonly referred to as the Girardi Group. This includes Jerome Falk, who was appointed by the State Bar to be the special prosecutor in the State Bar disciplinary case against Girardi and Lack.

Falk did not disclose on the record that he and his firm were long time personal attorneys for Girardi and Lack, including with respect to the misappropriation of $20 million of class members’ moneys rom the settlement of a San Diego Superior Court class action. Falk and his firm Howard Rice did not disclose to Doe when they were representing Doe that they also represented Girardi and Girardi & Keese. Howard Rice requested Doe to provide them under an attorney/client relationship with information as to moneys misappropriated by Girardi from class actions and mass settlements, as well as similar fraud schemes to that practiced against Dole Fruit Company. This information that was provided in confidence to Howard Rice was provided to Girardi by said Howard Rice and their attorneys.

Girardi and Miller then conceived a corrupt plan and scheme to try and shut Doe up to prevent him from testifying in the federal disciplinary case against Girardi and in conjunction with major misappropriations of client moneys in multi-million dollar settlements and without paying the super priority medical liens in connection therewith in excess of billions of dollars. Girardi instigated the State Bar proceedings and offered a judgship in the Los Angeles Superior Court to O’Brien to intentionally default Doe and to cause him to be falsely charged with fabricated crimes, even though he was innocent and had prevailed in the parallel civil cases.

Girardi has continued to seek disbarment sub rosa with respect to his co-counsel in litigation after Girardi is caught settling cases for moneys that belong to the clients and not Mr. Girardi. For example, Girardi received sub rosa more than $50 million in the Erin Brockovich case, which was reported to Mr. Doe by multiple attorneys in connection with those transactions. Girardi misappropriated more than $120 million in connection with the Gutierrez class action in a published opinion, Gutierrez v. Girardi, (2011) 194 Cal.App.4th 925. Girardi was involved in massive illegal campaign contributions to the John Edwards national campaign for President and in other election campaigns, including elections of judges of the Los Angeles Superior Court. Girardi had his private investigator Tom Layton put on the State Bar payroll to be used to dig up dirt against his opponents and to intervene on behalf of candidates for judgeships with the Governor to secure their appointment, without disclosure that they were hand picked by Girardi.

D. Girardi’s State Bar Connections

Girardi cemented his power broker status and political connections with the State Bar hierarchy with the use of illegal contributions and funding to supplement their income. He supported each State Bar chief trial counsel with illegal contributions that were not reported for income tax purposes. This included former State Bar Chief Prosecutor Michael Nisperos for whom Girardi underwrote his extensive illegal drug consumption, including heroin. Girardi illegally funded the campaigns of Joe Dunn with Medicare Trust Funds and other illegal contributions. Girardi gave massive gifts to the State Bar hierarchy, including the use of his private planes for their transportation, including Beth Jay and Joe Dunn. Girardi personally intervened on behalf of his clients, such as Ron Burkle, to fabricate State Bar cases against Burkle’s opponents. Girardi withheld major settlements from Doe’s former clients, without providing them an accounting or copies of the settlements when they occurred and utilized a substantial portion of that money to fund illegal contributions in judicial campaigns to put his friends on the court and to funnel moneys illegally to politicians that he controlled and would reward Girardi with financial favors.

Girardi, Miller and the Girardi Organization control the State Bar through its inter-relationship with the Judicial Council and CSC, including the extensive relationship with the former Chief Justice George and with the present personal counsel Beth Jay to the current Chief Justice and former Justice George.

The major misappropriation of moneys by the Administration of Courts (AOC) is traceable directly to those who were appointed at the direction of Girardi to executive positions with the AOC. Girardi is known as the banker with regard to class action and complex lawsuits filed in the Los Angeles Superior Court, whose complex department is commonly referred to as the bank. In one recent case, Girardi did not disclose his personal relationship with the chief opposing counsel, who made arrangements to give Girardi $90 million for essentially services that were never performed and to defraud the insureds of Farmers Insurance Co. in excess of one billion dollars. None of the judges of the complex department disclosed on their economic forms 700 the receipt of millions of dollars from Girardi over multiple years, which is why Girardi is known as the banker nationwide. He is also the banker for the State Bar and the State Bar Foundation. He has also arranged for unlawful moneys to be paid to State Bar officials, including the Executive Director of the State Bar and the former head of State Bar Discipline Judy Johnson, her friends and associates.

Girardi did not disclose that he was actively seeking a federal judgeship for Rory Little, the special prosecutor in his disciplinary case, and had personally intervened with multiple U.S. Senators on his behalf. Girardi also did not disclose his relationship with Little’s wife and her law firm when he sought the appointment as the special prosecutor in his case. Additionally, Girardi sought intervention to appoint the current President of the State Bar to a federal judgeship who assisted Girardi in connection with the appointment of Little as the special prosecutor in Girardi’s discipline case, knowing that Mrs. Little was a partner of that firm.

E. The Politically Connected Thomas Girardi Is Found Not Culpable by the State Bar – Contrary to the Decision of this Court

The politically connected Girardi, Lack and Paul Traina were sanctioned $390,000 and admonished and/or suspended by the Ninth Circuit for committing fraud on the court, but never subjected to any proceeding or discipline by the State Bar. Due to Girardi being the law partner of State Bar President Miller and Miller’s involvement in the fraudulent matter, a State Bar insider and colleague of Miller’s, Falk of the Howard Rice firm, was appointed as a special prosecutor. [Falk’s partner Douglas Winthrop is an officer of the State Bar and serves on the Board of the California Bar Foundation with Miller.] Falk then ignored the Ninth Circuit findings that these lawyers committed a fraud on the Court.

In the Ninth Circuit, special master Judge A. Wallace Tashima concluded Girardi “reckessly” made false statements, while Lack and Traina acted “knowingly, intentionally and recklessly” and assessed sanctions ($390,000), which the offending firms and lawyers did not oppose. However, based on the lawyers’ objections to the findings regarding their intent to defraud the Court, the Ninth Circuit appointed Hastings law professor Little as a special prosecutor, who found Judge Tashima’s findings to be “accurate and provable by clear and convincing evidence.” The Ninth Circuit then adopted Judge Tashima’s report and conclusions in a published opinion – In re Girardi, 611 Fed.3d 1027, 1039-1040 (2006).

“The history of the enforcement action demonstrates the multiple occasions on which they chose to remain willfully blind to the fact that they were making false statements. By the time they appeared in this court, the attempt to salvage their case became indistinguishable from a knowing submission of false documents. Suspension is the appropriate discipline for these Respondents . . . Respondents in this case have been respected members of the bar, and each has presented significant mitigating evidence. Their conduct in this case, however, cannot be excused on that basis, given their culpability and the substantial injury their conduct caused the opposing parties and this court. We have carefully considered the recommendations of Judge Tashima and Professor Little, who have made our task substantially easier and whose assistance we gratefully acknowledge. We impose discipline as follows:

THOMAS V. GIRARDI is formally reprimanded.

WALTER J. LACK and PAUL A. TRAINA are suspended from practice before the Ninth Circuit for six months.

These disciplinary orders and findings satisfy the State Bar’s standard of proof for imposing discipline and are considered res judicata (proven), which State Bar respondents are collaterally estopped from denying or disputing. (§6049.1; In re Kittrell, supra, 4 Cal. State Bar Ct. Rptr. 195, p.7.) Regardless, the State Bar and Falk exonerated these lawyers solely on political grounds.

Thus, without having been found to have engaged in misconduct by any constitutional court, Doe is severely disciplined [disbarred]; whereas, the State Bar exonerated Girardi, Lack and Traina; all of whom were found to have engaged in severe misconduct by this Court.

The State Bar’s pursuit of charges against Gottschalk on such an improper and selective basis constitutes an egregious abuse of the prosecutor’s duties and a denial of due process. (Freeman v. City of Santa Ana (9th Cir. 1995) 68 Fed.3d 1180, 1187.) As arm of the California Supreme Court, the State Bar must regulate “impartially” to ensure that “justice shall be done.” (Berger v. United States (1935) 295 U.S. 78, 85, 88 [government not “an ordinary party,” but is a ‘sovereignty whose obligation to govern impartially is as compelling as its obligation to govern at all; and whose interest, therefore, in a criminal prosecution is not that it shall win a case, but that justice shall be done”].) Plainly, that was not done here.

III. ARGUMENT

Knowing Doe could prove Girardi’s criminal malfeasance, Girardi assert his considerable influence over the State Bar to have Gottschalk subject to an unconstitutional default and disbarment.

A. In re Rose Allows Unconstitutional Defaults

The default strategy used against Gottschalk is void, as a matter of law, because he filed an answer to the disciplinary charges. See English v. IKON (2001) 94 Cal.App.4th 130, 143:

A “default judgment” within the meaning of section 473(b) is a judgment entered after the defendant has failed to answer the complaint and the defendant’s default has been entered. (See Code Civ. Proc., § 585 [setting forth procedures for entry of default judgment]; Peltier v. McCloud River R.R. Co., supra, 34 Cal.App.4th at p. 1820, 41 Cal.Rptr.2d 182 [“a default judgment is entered when a defendant fails to appear”].)

Doe’s Petition for Review to the CSC briefed the issue of the entry of the ultra vires – void default, which denied him a hearing on the merits in the State Bar. Regardless, the CSC issued a summary denial.

1. A Party Who Has Appeared in a Proceeding Cannot be Defaulted

The default was entered under former State Bar Rules of Procedure (SBRP) 201, which is unconstitutional, because it allowed a default based on the failure to appear at trial. However, the failure to appear at trial is grounds for contempt – not entry of default.

No court can enter a default at trial where a defendant has appeared and filed an answer. (See Heidary v. Yadollahi (2002) 99 Cal.App.4th 857, 864 [“Where a defendant has filed an answer, neither the clerk nor the court has the power to enter a default based upon the defendant’s failure to appear at trial, and a default entered after the answer has been filed is void”]; Wilson v. Goldman (1969) 274 Cal.App.2d 573, 576-578 [where answer filed, default order based on failure to appear at trial is “void on its face” and thus subject to direct or collateral attack at any time].) (See Fed. Rule Civ. Proc. 55(b)(1); Direct Mail Specialists, Inc. v. Eclat Computerized Technologies, Inc. (9th Cir. 1988) 840 Fed.2d 685, 689 [if defendant has appeared in the action, a clerk-entered default judgment is “void ab initio.”]. Moreover, the policy of the law is it have every litigated cause tried on its merits. (See Barri v. Rigero, 168 Cal 736, 740 (1914).) Thus, by void default, the State Bar deemed all of the unproven charges to be admitted in violation of State Bar Act – §6088 [limiting grounds for deeming facts admitted]; Matter of Frazier (Rev.Dept. 1991) 1 Cal. State Bar Rptr. 676, 697 [Hearing Department judge “did not have the direct power of contempt, nor could he exercise the authority to strike respondent’s answer and deem the allegations at issue to have been admitted by default”].

2. The Failure to Appear at Trial Is an Alleged Contempt, which Must Be Adjudicated in the Superior Court

The default strategy to prevent Gottschalk from appearing at trial does not result in a default. Rather, it is an alleged contempt in violation of the trial subpoena, which requires referral from the State Bar to the Superior Court for adjudication. Of course, no ethical court could find Gottschalk in contempt, because of the default strategy used against him, which made it impossible for him to comply with the subpoena.

As referenced, the refusal to comply with a trial subpoena is an alleged contempt. (Code Civ. Proc. §1991.) Prior to the issuance of an order to show cause (OSC) re: contempt, the Superior Court must find (1) a valid (written) order; (2) that the alleged contemnor had knowledge of the order; (3) that the alleged contemnor had ability to comply with the order; and (4) that the alleged contemnor evidenced willful failure to comply with the order. Only after these four criteria are satisfied, then issue an OSC. (Code Civ. Proc. §§1212 & 1211.5.; Conn v. Superior Court (Farmers Group) (1987) 196 Cal.App.3d 774, 784).)

Pursuant to the mandatory duties specified in SBRP 152(b) & 1873, which require adherence section 1991 and State Bar Act – §§6049, 6050 & 6051, the Superior Court has exclusive jurisdiction to determine the alleged contempt in the State Bar. Thus, once the State Bar sought to enforce the trial subpoena against Doe, the State Bar Court had to refer the matter to the Superior Court for adjudication.

Rather than adhere to the mandatory duty to refer the alleged contempt to the Superior Court, the State Bar Court conferred new authority onto itself without and in excess of all jurisdiction, and entered the terminating sanctions (default) against Gottschalk. However, rule 152(b) states:

“Trial subpoenas are subject to the Business and Professions Code and to all provisions of Chapter 2 of Title III of Part IV of the Code of Civil Procedure (beginning with section 1985), except those pertaining to bench warrants and concealed witnesses, and except as modified or limited by these rules.” (Emphasis.)

Rule 152(b) specifies the State Bar must comply with sections 1985 through 1997 of “Chapter 2 of Title III of Part IV of the Code of Civil Procedure,” which includes controlling section 1991, but excludes the Civil Discovery Act4 from rule 152(b). Section 1991 limits the State Bar’s authority to enforcing subpoenas as an alleged contempt, which under rules 152(b) & 187 and sections 6049, 6050 & 6051, must be referred to an article VI court and can be only punished as a contempt and by way of monetary fine or coercive incarceration – not default. See People v. Gonzales (1966) 12 Cal.4th 804, 816-817.

Moreover, had the State Bar sought to enforce the subpoena, section1991 required it to move to compel the testimony through a contempt proceeding no “more than 20 days from the date of the refusal” to testify.”

5 Having failed to do so, the State Bar waived its right to enforce the subpoena in this matter and acted without any jurisdiction. Regardless, the State Bar enforced the trial subpoena through the ultra vires – void default (terminating sanctions). However, refusing to follow its mandatory duty does not allow the State Bar Court to create new procedural rules as a de facto Legislative body – extrapolating and fabricating in the spur of the moment and without any due process.

Moreover, the State Bar Court created a contempt, which cannot be expunged and is contrary to §6051, which allows for this eventuality.

“On the return of the attachment, and the production of the person attached, the superior court has jurisdiction of the matter, and the person charged may purge himself or herself of the contempt in the same way, and the same proceedings shall be had, and the same penalties may be imposed, and the same punishment inflicted, as in the case of a witness subpoenaed to appear and give evidence on the trial of a civil cause before a superior court.” (Emphasis.)

In Jacobs v. State Bar (1977) 20 Cal.3d 191, the Supreme Court held the provisions of §6051 are “directory” in enforcing an investigation subpoena — only where the State Bar does not attempt to enforce the subpoena.

“The State Bar accordingly urges us to hold that the superior court’s jurisdiction is limited to cases in which enforcement of subpoenas is sought.” (Id., at 196.)

“Section 6051, upon which Jacobs primarily relies, clearly seems restricted to contempt proceedings initiated by the State Bar to enforce compliance with its subpoenas.” (Id., at 197.)

“We construe the use of the word “shall” as directory in this context, for certainly the Legislature did not intend to foreclose the State Bar or local committee from exercising its discretion in determining whether or not to enforce a subpoena.” (Id., at 197.)

“We hold that, unless and until the State Bar seeks to enforce its subpoena, superior courts have no jurisdiction to review the validity thereof.” (Id., at 198.)

See also, McKnew v. Superior Court (1943) 23 Cal.2d 58, 67:

“Section 6051 of the Business and Professions Code makes it the duty of the chairman of a local administrative committee which has a disciplinary proceeding pending before it, to “report the fact that a person under subpoena is in contempt of the … committee to the superior court in and for the county in which the proceeding … is being conducted and thereupon the court shall issue an attachment … directed to the sheriff … commanding the sheriff to attach such person and forthwith bring him before the court.” (Emphasis.)

See also discussion in Rutter, Professional Responsibility §§11:717-20:

§11:720] Comment: The State Bar Court has no power to impose a fine or imprisonment for contempt. Therefore, although the statute does not expressly say so, the contempt proceedings must be referred to the local superior court.

[Cross-refer: Contempt of court procedure is discussed in Wegner, Fairbank, Epstein & Chernow, Cal. Prac. Guide: Civil Trials & Evidence (TRG), Ch. 12.]

The State Bar took this very position, resulting in judicial admissions, in its petition to the Supreme Court and underlying brief and request for modification in the underlying Jacobs appeal. (See RJN, Ex. 2, State Bar Verified – Petition for Review, Appellate Brief and Request for Modification in Jacobs v. State Bar.)

In its Jacobs Petition, the State Bar admitted:

While the State Bar is under a duty to report contempt of its subpoenas to the appropriate superior court pursuant to section 6051, State Bar subpoenas may be issued at the request of respondent attorneys as well as State Bar examiners or staff attorneys.

(Petition, pg. 2.)

Such a construction of the provisions of section 6051 is consistent with the only reported appellate case under the section: McKnew v. Superior Court (1943) 23 Cal.2d 58. In this case, Mr. McKnew testified before a State Bar local administrative committee, but refused to answer certain questions (23 Cal.2d, at p. 61). The local administrative committee “originate[d] contempt proceedings against him” in the superior court pursuant to section 6051 (23 Cal.2d, at pp. 67 and 61), which proceedings “resulted in an order [of the superior court] directing him to answer the questions.” 23 Cal.2d, at p. 61.

(Id., 10.)

It is evident from this original language of the State Bar Act that the Legislature did not intend the State Bar to have power to enforce its own subpoenas. Instead, the Legislature intended that the contempt powers of the superior courts be used to enforce State Bar subpoenas and limited the State Bar’s role to reporting the fact of contempt of a State Bar subpoena to the appropriate superior court.

(Id., 14.)

In light of the clear language of section 6051 and its legislative history, the construction evident in the Court of Appeal’s opinion amounts to a wholesale rewriting of the section by that court. Such action is unconstitutional because the legislative power of this state is vested in the Legislature, not the courts.

Cal. Const., Art. IV, §l. As this Court said in Estate of Simmons (1966) 64 Cal.2d 217, 221 [4]:

“When the words of the statute are clear, the court should not add to or alter them to accomplish a purpose that does not appear on the face of the statute or from its legislative history. [Citations omitted.]”

(Id., 15.)

In its Jacobs Appellate Brief:

But a careful examination of the provisions of section 6051 reveals that it does no such thing. The section merely provides a means whereby the State Bar can obtain the assistance of a superior court in enforcing a State Bar subpoena.

(Brief, pg. 21.)

The ruling of the article VI court in a contempt proceeding cannot be reviewed by any other court. (See People v. Latimer (1911) 160 Cal. 716, 720.6) Knowing that it could not appeal from the ruling of the Superior Court, in which Doe would be allowed to present evidence of the default strategy and/or cure the default, the State Bar violated this mandatory duty to refer the alleged contempt to the Superior Court’s jurisdiction.

3. The Default Violates State Bar Precedent The default further disregards the controlling State Bar case of Matter of Frazier (Rev.Dept. 1991) 1 Cal. State Bar Ct.Rptr. 676, 697, which held:

“However, even the examiner (State Bar) concedes that the hearing referee did not have the direct power of contempt (Bus. & Prof.Code, § 6051) nor could he exercise the authority to strike respondent’s answer and deem the allegations at issue to have been admitted by default as a matter of law. Those latter remedies were not available as sanctions in the discovery phase of the proceeding (rule 321, Rules Proc. of State Bar); and, in our view, the referee had no authority to invoke them as a sanction for failure to testify at the hearing. Therefore, we disagree with the referee’s striking of respondent’s answer to count five of the notice to show cause and find instead that respondent has not admitted the allegations therein.” (Emphasis.)

Moreover, despite that Doe sought to vacate the default, the State Bar Court denied him the relief to be afforded under Code Civ. Proc. §§473(b)&(d) and SBRP 203.

4. The Default Violates the State Bar Act

The default declared all of the unproven charges against Doe to be admitted as true in violation of State Bar Act – §6088. However, section 6088 limits the power of the State Bar Court to admit facts on the following grounds:

“The board may provide by rule that alleged facts in a proceeding are admitted upon failure to answer, failure to appear at formal hearing, or failure to deny matters specified in a request for admissions; the party in whose favor the facts are admitted shall not be required to otherwise prove any facts so admitted. However, the rules shall provide a fair opportunity for the party against whom facts are admitted to be relieved of the admission upon a satisfactory showing, made within 30 days of notice that facts are admitted, that (a) the admissions were the result of mistake or excusable neglect, and (b) the admitted facts are actually denied by the party.”

As discussed, Doe, having appeared through his Answer, does not allow the State Bar Court to have declared the charges to be admitted by default, without any federal constitutional – due process to be afforded to respondents to present a defense, cross-examine witnesses, present direct-examination and evidence, trial on the merits, oral argument and written decisions of the Hearing and Review Departments of the State Bar Court in violation of the State Bar Act – §6085.

See Giddens v. State Bar (1981) 28 Cal.3d 730, 735:

“The circumstances of this case underscore the fact that a fair hearing did not take place. Petitioner was not afforded the right to defend against the charge by the introduction of evidence.” (Bus. & Prof.Code, s 6085, subd. (a).) Although petitioner challenged the veracity of the complainants’ testimony, he never had an opportunity to cross-examine those witnesses. Since petitioner participated in the very meetings those witnesses discussed, his presence at the hearing might well have ensured the full and fair presentation of all the facts. Additionally, since he was not present to testify, the hearing officers could not evaluate his demeanor and credibility. The issue before the bar was petitioner’s continued suitability for legal practice. Without any representation of petitioner’s views, a fair hearing was not possible.” (Emphasis.)

This has resulted in the State Bar Court engaging in Sophistry by claiming it has made findings of fact, credibility and character in an uncontested proceeding, which has unlawfully taken away Doe’s property interest in the right to practice law through a default strategy. See” Conway v. State Bar (1989) 47 Cal.3d 1107 B. In Re Rose Allows Political Prosecutions, Violations of Constitutional – Due Process and Criminal Malfeasance

Doe’s Petition provided incontrovertible evidence that the State Bar, which is the administrative arm of the CSC7 was engaging in a political prosecution to aid Mr. Girardi. Regardless, the CSC issued a summary denial.

1. Since In re Rose, No Respondent Petitions Have Been Granted

The possibility of any respondent8 obtaining review by the CSC for twelve (11) years has been proven to be illusory. That “opportunity” for review is illusory [fraudulent], is supported by former Justice Brown’s dissent in In re Rose, 22 Cal.4th at 466-470, in which she explained that the real purpose of In re Rose is to allow the CSC to “wash its hands” of the lawyer discipline system review process, in which all State Bar recommendations are pro forma upheld through the summary denial of all petitions for writ of review filed by respondents. The negative consequences “antithetical to the constitutional design” discussed in Justice Brown’s dissent and the above referenced treatise, have come to pass under the current disciplinary system, in which attorneys are, among other things, being denied their right to genuine and impartial judicial review, with far-reaching and deleterious consequences on an attorney’s right to pursue a livelihood and their reputations, in addition to harming their clients by allowing the State Bar to attack and lie about successful verdicts, in favor of, and on behalf of losing defendants, and trial courts who were reversed. In other words, the CSC has abdicated its duties of review specified in In re Rose by never granting review on behalf of respondents regardless of the record placed before it in a petition.

2. In re Rose Allows the State Bar to Violate Constitutional – Due Process Rights and Privileges without Comment

Since In re Rose, the State Bar has refused to follow binding constitutional – due process, federal precedent, CSC precedent, State Bar precedent, State Bar Act – Bus. & Prof. Code §§6000, et seq. and SBRP. See for example:

Spevack v. Klein, 385 U.S. 511, 514 (1967) [“the Self-Incrimination Clause of the Fifth Amendment has been absorbed in the Fourteenth, that it extends its protection to lawyers as well as to other individuals, and that it should not be watered down by imposing the dishonor of disbarment and the deprivation of a livelihood as a price for asserting it.” (Emphasis)];

Lady v. Worthingham (1943) 61 Cal.App.2d 780, 782 [decisions and judgments of the Courts of Appeal and the Supreme Court are not subject to review by the State Bar or a committee thereof];

Clemente v. State of California (1985) 40 Cal.3d 202, 210-213 [ the “law of the case doctrine” bars a court from allowing any redetermination of legal issues previously decided by the courts of appeal, whether in a published or unpublished decision];

In re Kittrell (2000) 4 Cal. State Bar Ct. Rptr. 195, 206, [“. . .we conclude that principles of collateral estoppel can properly be applied in this (State Bar Court) proceeding. . .”];

Matter of Anderson (1997) 3 Cal. State Bar Ct. Rptr. 775, 785 – citing U.S.A. v. Wunsch (9th Cir. 1996) 84 Fed.3d 1110 [lawyer cannot be found culpable for so-called “offensive personality”9 and making false statements without establishing the statements are knowingly false];

Gentile v. State Bar of Nevada (1991) 501 U.S. 1030, 1077-1078 [“The void-for-vagueness doctrine is concerned with a defendant’s right to fair notice and adequate warning that his conduct runs afoul of the law. (Citations.)”];

Matter of Mapps (1990) 1 Cal. State Bar Ct. Rprt. 19, 24 [an attorney cannot be disciplined for uncharged Penal Code violations];

In re Carr (1992) 2 Cal. State Bar Ct. Rptr. 244, 254 [“Taking judicial notice of court records does not mean noticing the existence of facts asserted in the documents in the court file; a court cannot take judicial notice of the truth of hearsay just because it is part of a court record. (citations.)”];

Brady v. Maryland (1963) 373 U.S. 83, 87; In re Lessard (1965) 62 Cal.2d 497, 508-509 [prosecution must, without request, disclose substantial material evidence favorable to the accused];

Standing Committee v. Yagman (9th Cir. 1995) 55 Fed.3d 1430, 1441, 1437

[advocacy protected by the First Amendment – not constrained by rules of professional conduct];

Jacobs v. State Bar (1977) 20 Cal.3d 191, 197-198 [State Bar enforcement of subpoena creates jurisdiction in Superior Court, not the State Bar or the Supreme Court];

Matter of Frazier (Rev.Dept. 1991) 1 Cal. State Bar Ct.Rptr. 676, 696

[no entry of terminating sanctions [default] for refusing to testify in State Bar proceeding];

Matter of Lapin (Rev.Dept. 1993) 2 Cal. State Bar Ct.Rptr. 279, 295; McKnew v. Superior Court (1943) 23 Cal.2d 58, 67 [State Bar Court lacks contempt or sanction power – requiring referral to Superior Court];

Summerville v. Kelliher (1904) 144 Cal.155, 160 [unconstitutional to strike answer for refusing to testify].

Regardless, no court has issued any decisions critical of unconstitutional [criminal] State Bar practices.

3. In re Rose Allows the State Bar to Engage in Criminal Malfeasance with Immunity

In re Rose allows the State Bar to ignore the above-referenced law and rules of procedure to engage in brazen criminal malfeasance — knowing that its actions will never be questioned, examined or scrutinized. Moreover, the State Bar engages in selective malicious prosecutions against solo or small firm practitioners, as opposed to large and/or politically connected lawyers, such as Mr. Girardi, and firms representing corporate interests. This case involving Mr. Doe serves an exemplar as to what lengths the State Bar will go to pursue political prosecutions and the harm it can inflict.

IV. ANALYTICAL ARGUMENT

A. The Unconstitutional Holding of In re Rose

See In re Rose, supra, at 430:

The court held that this type of decision does not invest the State Bar Court with judicial power, nor does it deprive an attorney of a right to an independent determination by a court vested with judicial power by Cal. Const., art. VI. The Supreme Court exercises its independent judgment as to the weight and sufficiency of the evidence and as to the discipline to be imposed, and properly utilizes the State Bar Court as its administrative arm to conduct the preliminary investigation, hearing, and determination of complaints. The court further held that the summary denial was not a cause within the meaning of Cal. Const., art. VI, § 14, which requires that causes before the court be in writing with reasons stated, and that Cal. Const., art. VI, § 2, does not confer an independent right to oral argument in this context. The court also held that the summary denial did not deprive the attorney of his federal constitutional right to procedural due process, since it necessarily included a judicial determination on the merits . . . (Emphasis.)

A detailed analysis of the history of the disciplinary system and denial of constitutional – due process based on In re Rose’s summary denial without oral argument and written decision is discussed in Journal of Legal Advocacy and Practice treatise. (See RJN, Ex.1, 4 J. Legal Advoc. & Prac. 137 [Protecting Those Who Protect Others: The Implications of the Stat Bar Act on Attorneys’ Adjudication Rights in Disciplinary Proceedings].)

As discussed, the possibility of obtaining meaningful remedial review by the CSC for twelve (11) years has been proven to be illusory, which renders In re Rose unconstitutional. This established fact that “opportunity” for review is illusory, is supported by former Supreme Court Justice Janice Brown’s prescient dissent in In re Rose, 22 Cal.4th at 466-470.

Dissenting.-Reluctantly, even ambivalently, I dissent. They say hard cases make bad law; the result here, however, is foreordained: the majority reaches the only provident conclusion possible in the current circumstances. But it is also true that, underlying its reasoning and result, one has to wonder at the practical value of what this court does under the procedures now prevailing in bar discipline cases. As the court itself has acknowledged only recently, changes in our own rules made in the wake of legislative amendments to the administrative procedures governing bar discipline proceedings “relieve the court of the burden of intense scrutiny of all disciplinary recommendations.” (Cal. Supreme Ct., Invitation to Comment- Proposed Adoption of Rule 951.5, Cal. Rules of Court (Nov. 23, 1999) p. 2; see also Cal. Supreme Ct., Practices and Proc. (1997 rev.) pp. 3, 18-19, 25-26.) Moreover, the matrix of grantable issues identified in California Rules of Court, rule 954 appears to truncate the scope of our review. And in cases where no writ is sought, we usually content ourselves with less than that measure of “review.” Unless, by dint of skill or luck, the issues are framed so they are deemed to fall within the ambit of rule 954, an attorney facing suspension or disbarment from the right to practice her profession gets no hearing, no opportunity for oral argument, and no written statement of reasons-from this or any other article VI court. (Cal. Const., art. VI, § 14; hereafter article VI.) Instead, she gets a summary denial of review, the one-line order. Is that enough? Regrettably, it seems that, for now at least, it will have to do. . . .

Nothing so well illustrates the through-the-looking-glass quality of the majority’s reasoning as its rejection of petitioner’s claim that his case qualifies as a “cause” under article VI and must be decided “in writing with reasons stated.” The majority’s reasoning is fine, as far as it goes. It omits, however, an observation that ought to be decisive: this court is the only judicial body involved in the attorney discipline process. An attorney’s petition for review to this court marks the first and only time in the disciplinary process that article VI judges are asked to enter the case. For that reason, and for that reason alone, our decision, even if it is a summary denial of review, necessarily decides a cause. The majority makes an able attempt to paper over this reality, but in doing so it is compelled to adopt an empty formalism. . . .

Alas, attorneys faced with the loss of their livelihoods must now make do with the State Bar Court-an entity performing judicial functions but, despite the competence of its members, exercising no judicial powers-and our summary denials, unless the petition can be said to satisfy the criteria of rule 954. Yet the majority continues to pay lip service to the old regime, even using the same words and citing the same cases to paste over a hollowing-out of meaningful judicial review. We have tinkered with our rules so that it appears nothing has changed. But these are only words; the reality is different. In point of practice, in bar disciplinary cases in which we decline to grant review, we issue a pro forma order executing the State Bar Court’s “recommended” discipline. (See rule 954(a).) In those cases where review is not sought, it is questionable whether any judicial act of substance takes place. (Emphasis.)

As discussed, the negative consequences “antithetical to the constitutional design” discussed in Justice Brown’s dissent have been proven through the CSC’s abandonment of its duties of review specified in In re Rose by never granting review on behalf of respondents.

B. In re Rose Is Unconstitutional Because It Determines a “Cause” without Oral Argument and a Written Decision

Mr. Doe’s CSC Petition involved the “cause” of the ultra vires – void contempt [order to show cause (OSC)] for failure to appeal at trial and default determined by the State Bar and CSC without jurisdiction. (See In re Mazoros, 76 Cal.App.3d 50, 52-52 [once an order to show cause [re: contempt] or alternative writ issues, however, the matter becomes a “cause,” pursuant to the Cal. Const. Art. VI, Sec.14, and requires a written opinion]. However, In re Rose held no oral argument or written decision were required, because the CSC does not determine a “cause” in a petition. (See In re Rose, supra, at 448-449.)

Prior to In re Rose, the CSC held that the filing of the disciplinary charges is an OSC; thereby, requiring a written decision. (See Middleton v. State Bar, 51 Cal.3d 548, 558 (1990) [“notice to show cause”]; Jacobs v. State Bar, 20 Cal.3d 191, 196 (1977):

Preliminary investigations are informal matters conducted in confidence for the purpose of determining whether probable cause exists to issue an order to show cause. (Former rule 21(a); present rule 12.10.) Such an order marks the commencement of formal disciplinary action. (Former rule 25; present rule 14.20.) (Emphasis.)

See also, In Re Heron, 212 Cal. 196, 197-198:

The proceeding was brought to issue by informal complaints made to the board of governors and the local administrative committee of the State Bar. Investigation of the charges was thereafter made, resulting in a notice or order to show cause, specifying the said charges, and fixing the date and hour for a hearing thereon. Petitioner does not complain of lack of notice, nor does he complain of any deprivation of the right to know the character of the accusations nor of lack of time to prepare his defense through counsel or to produce evidence nor of lack of opportunity to examine and cross-examine witnesses. (Emphasis.)

(See Evid. Code §451(e)10.) An OSC is a “cause” within the meaning of Cal. Const., art. VI, § 14, which requires that causes before a court be in writing with reasons stated [written decision]. (See In re Mazoros, supra, 76 Cal.App.3d at 52-53.)

C. In re Rose Denies Constitutional – Due Process Rights

In re Kramer, 193 Fed.3d 1131, 1132-1333 (1999) states:

In Selling v. Radford, 243 U.S. 46, 50-51, 37 S.Ct. 377, 61 L.Ed. 585 (1917), the Court held that a federal court could impose reciprocal discipline on a member of its bar based on a state’s disciplinary adjudication, if an independent review of the record reveals: (1) no deprivation of due process; (2) sufficient proof of misconduct; and (3) no grave injustice would result from the imposition of such discipline. Thus, while federal courts generally lack subject matter jurisdiction to review the state court decisions, see D.C. Court of Appeals v. Feldman, 460 U.S. 462, 486, 103 S.Ct. 1303, 75 L.Ed.2d 206 (1983); Rooker v. Fidelity Trust Co., 263 U.S. 413, 415-16, 44 S.Ct. 149, 68 L.Ed. 362 (1923), a federal court may “examine a state court disciplinary proceeding if the state court’s order is offered as the basis for suspending or disbarring an attorney from practice before a federal court.” MacKay v. Nesbett, 412 F.2d 846, 847 (9th Cir.1969) (citing Theard v. United States, 354 U.S. at 281-82, 77 S.Ct. 1274).

In re Rose, supra, at 459, specifies the following criteria to grant review:

Our order to show cause directed petitioner and the State Bar to address the criteria the court may employ in determining whether to grant a petition for review of a State Bar Court decision recommending disbarment or suspension. The State Bar asserts that in the vast majority of cases, issues warranting review are likely to fall within the categories set forth in rule 954(a)11. As explained previously, rule 954(a) provides that we will order review of such a decision “when it appears (1) necessary to settle important questions of law; (2) the State Bar Court has acted without or in excess of jurisdiction; (3) petitioner did not receive a fair hearing; (4) the decision is not supported by the weight of the evidence; or (5) the recommended discipline is not appropriate in light of the record as a whole.” According to the State Bar, in extraordinary circumstances where an issue warranting review does not meet the criteria specified in the rule, we may exercise our inherent authority to review such a question. (See rule 951(g) [“Nothing in these rules shall be construed as affecting the power of the Supreme Court to exercise its inherent jurisdiction over the lawyer discipline and admissions system”].)

Despite the existence of all five (5) criteria, extraordinary issues involving the political prosecution of Doe on behalf of Girardi and existence of the “cause” of contempt for failure to appear at trial – resulting in the default briefed in the Petition, the CSC issued a summary denial contrary to its holding in In re Rose.

D. In re Rose Is Unconstitutional Because the CSC Condones the Institutional Denial of 5th Amendment Rights in the State Bar

The State Bar has instituted a policy12 [discussed below] to deny respondents their rights under the under the 5th Amendment. To prevent this specific abuse, in 1999, the California Legislature amended §§6068(i), 6079.4 and 6085(e) of the State Bar Act, and expressly added to these statutes the right to assert the 5th Amendment in State Bar proceedings. (See Legislative History: 1999 Cal. Legis. Serv. Ch. 221 (S.B. 143); California Bill Analysis, S.B. 143 Sen., 6/24/1999.)

State Bar Act- §6068(i):

To cooperate and participate in any disciplinary investigation or other regulatory or disciplinary proceeding pending against himself or herself. However, this subdivision shall not be construed to deprive an attorney of any privilege guaranteed by the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, or any other constitutional or statutory privileges. This subdivision shall not be construed to require an attorney to cooperate with a request that requires him or her to waive any constitutional or statutory privilege or to comply with a request for information or other matters within an unreasonable period of time in light of the time constraints of the attorney’s practice. Any exercise by an attorney of any constitutional or statutory privilege shall not be used against the attorney in a regulatory or disciplinary proceeding against him or her.

The State Bar’s policy eviscerates 5th Amendment rights.

In Spielbauer v. County of Santa Clara, 45 Cal.4th 704, 719-720 (2009), the

California Supreme Court cited to the holding in Spevack v. Klein, 385 U.S. 511, 514 (1967) [“the Self-Incrimination Clause of the Fifth Amendment has been absorbed in the Fourteenth, that it extends its protection to lawyers as well as to other individuals, and that it should not be watered down by imposing the dishonor of disbarment and the deprivation of a livelihood as a price for asserting it.”].) (Emphasis.) See also, In re Warburgh, 644 Fed.3d 173, 177, FN3 [attorney’s refusal to answer questions or produce evidence in a disciplinary proceeding protected by the 5th privilege against self-incrimination, citing to Spevack v. Klein, supra, 385 U.S. at 516, 520].)

As referenced, despite the clear and binding [constitutional] authority affording attorneys the right to assert the 5th Amendment, the State Bar, as the administrative arm of the CSC [In re Rose, supra, at 438] has an institutional policy denying 5th Amendment rights to respondents. In an article appearing in Los Angeles Lawyer, April 2010, the State Bar declared:

“The respondent does not have the right to refuse to testify.” [FN23 Goldman v. State Bar, 20 Cal. 3d 130, 140 (1977)]:

“Next, petitioners argue that their rights under the federal and state Constitutions (U.S.Const., Amends. V and XIV; Cal.Const., art. I, former s 13, now s 15) were violated because they were compelled to testify against themselves and to produce records in this proceeding. This court rejected similar contentions in Black v. State Bar (1972) 7 Cal.3d 676, 103 Cal.Rptr. 288, 499 P.2d 968 on the ground that an attorney in a disciplinary proceeding does not have the same immunities as a defendant in a criminal proceeding. The reasoning in Black is equally applicable here.”

(See RJN, Ex. 3, 33-APR LALAW 28, BEFORE THE BAR, [Failure to Cooperate with the State Bar Enforcement Division Can Transform a Minor Complaint into a Major Disciplinary Matter], by Manuel Jimenez, deputy trial counsel with the State Bar of California.)

However, Goldman and Black, decided in 1977 and 1972, are no longer controlling based on Spielbauer, and the subsequent statutes adopted expressly by the Legislature, while having been unconstitutional based on Spevack. Regardless, the State Bar [administrative arm of the CSC] refuses to afford this seminal constitutional right in violation of the United States and California Constitutions, California Legislature, and United States Supreme Court, while adopting a policy that it intends to violate the 5th Amendment rights of all respondents. In addition to rendering In re Rose unconstitutional, this institutional policy makes a mockery of Hirsch v. Justices of the Supreme Court of the State of California, 67 Fed.3d 708, 713:

3. Opportunity to Present Federal Claims

The California Constitution precludes the Bar Court from considering federal constitutional claims. See Calif. Const. art. III, § 3.5. However, such claims may be raised in judicial review of the Bar Court’s decision. This opportunity satisfies the third requirement of Younger. See Ohio Civil Rights Comm’n v. Dayton Christian Schools, Inc., 477 U.S. 619, 629, 106 S.Ct. 2718, 2723-2724, 91 L.Ed.2d 512 (1986); Kenneally v. Lungren, 967 F.2d 329, 332 (9th Cir.1992).)

However, Hirsh was decided before In re Rose replaced oral argument and written decisions, with pro forma summary denials. Moreover, this lack of constitutional review violates this Court’s holding in In re Kramer, supra, 193 Fed.3d at 1132.)

E. In re Rose Is Unconstitutional Because It Condones the Framing of Respondents

As the administrative arm of the CSC, the State Bar framed Doe and used an unconstitutional ultra vires void default strategy to obtain findings of culpability, which were never reached by a constitutional court. These issues were briefed in Gottschalk’s CSC Petition. Moreover, in the Petition, the CSC was faced with the incontrovertible evidence that Gottschalk was denied due process, received no hearing on the merits, no review and there was no record to review. Regardless, the CSC issued a summary denial. Thus, either the CSC did not review the Petition or it condoned these abuses involving criminal violations of Doe 14th Amendment constitutional – due process rights. Either scenario requires this Court to render In re Rose unconstitutional.

F. In re Rose Denies Federal Constitutional Claims and Rights

When prosecutors are acting in their official capacity, but not performing prosecutorial functions [e.g., investigations], they are not protected by qualified immunity. (See U.S. Const., Art. VI§1983 claims13 [including the claims for declaratory and injunctive relief], which are based on the deprivation of federal constitutional rights, privileges and immunities [Const. Amend. XIV, § 114]. Regardless, based on In re Rose, the COA violated the Supremacy Clause by refusing to follow federal law regarding the §1983 claims. (See Catsouras v. Dept. of Cal. Highway Patrol, 181 Cal.App.4th 856, 891 (2010) citing Bach v. County of Butte, 147 Cal.App.3d 554, 563 (1983).) See also, Felder v. Casey (1988) 487 U.S. 131, 138.) Thus, §1983 preempts state law when it conflicts with the enforcement of federal rights.15 (See 8 Witkin, Sum. Law 10th (2005) Const. Law, § 821, p. 240:

The phrase “and laws” in 42 U.S.C., §1983 is not limited to civil rights or equal protection laws; the statute creates a cause of action for deprivation of any federal statutory right. (Citations.) . . .

The only exception to enforcement of a right under §1983 is where Congress enacted another statute for enforcement. (Id., see disc. in Witkin, §(2) Exception.) However, there is no federal law precluding the controlling enforcement of the federal §1983 rights and privileges for the declaratory and injunctive relief claims alleged in the Superior Court actions. See also, Del Rio v. Jetton, 55 Cal.App.4th 30, 33 (1997):

. . . when compliance with both state and federal law is impossible, [citation], or when the state law ‘stands as an obstacle to the accomplishment and execution of the full purposes and objectives of Congress,’ [Citations.]

If, in fact, all of the 8 Witkin, Summary 10th (2005) Const Law, §818, p.234 and cases cited; 2 Witkin, Cal. Proc. 5th (2008) Jurisd, § 291, p. 901 [Judgment Outside Issues in Contested Case] Court lacks jurisdiction in default proceeding to provide remedy of relief beyond pleading.) Moreover, if the State Bar had jurisdiction over these claims, it would have jurisdiction to grant declaratory and injunctive relief and award damages, under §1983. However, it has no such jurisdiction to determine the claims, nor does the CSC have the jurisdiction to grant declaratory and injunctive relief and/or award money damages in a petition for review. (See Hirsh, supra, at 712-713.) While it is patently ludicrous to even posit such a notion, the COA issued a decision with this holding.

2. In re Rose Imposes Criminal Fines and Punishment in Violation of the 5th and 6th Amendments

As discussed, State Bar costs have been determined to be a criminal fine (punishment) and non-dischargeable in bankruptcy. (See Findley v. State Bar of California, supra, 59 Fed.3d 1048; State Bar Act – §6086.10(e).) In addition, §6126(c) makes a disciplinary order a crime as well as §6126(d), which provides penalties for additional criminal punishment.

The burden of proof in State Bar proceedings, which are not tried before a jury or article VI court judge, is “clear and convincing” and not “beyond a reasonable doubt, as required in criminal proceedings. Moreover, criminal defendants cannot be “defaulted”, as occurred here. Rather, a criminal defendant is entitled to a jury trial before an article VI court judge, and is allowed the right to present evidence, cross-examine witnesses and to refuse to testify; all of which were denied here in violation of the 6th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and State Bar Act – §§6085, while exposing him to further criminal sanctions and punishment based on In re Rose, pursuant to §§6126(c)&(d).

3. The CSC Order of Disbarment Is Unenforceable Because It Is Based on a Void Default

Code Civ. Pro. §670(a) Code Civ. Proc. §670(a), because it cannot provide the required affidavit that Doe failed to “answer” the disciplinary charges. That such an affidavit is required further establishes the voidness of the default. Moreover, the State Bar neither warned Doe that it would seek or enter the terminating sanctions (default) nor allowed him to cure the default. (See Fasuyi v. Permatex, Inc., 167 Cal.App.4th 681, 694-696 (2008) [failure to warn a defendant or its attorney, as occurred here, that a default is about to be sought provides additional grounds for a court to grant relief from an alleged default].)

The default was entered without any notice to Doe, pursuant to Code Civ. Proc. §594 and without any notice of the costs to be assessed against him, which are the subject of default, further rendering it void. After the entry of the default, the State Bar obtained additional punishment based on matters not charged. This results in an amendment of the charges16, which vitiates the default, requires service of the new charges and affords Doe the right to answer and contest the charges. (See, e.g., Jackson v. Bank of America (1986) 188 Cal.App.3d 375, 387; Engebretson & Company, Inc. v. Harrison (1981) 125 Cal.App.3d 426, 443.) A default judgment for greater relief or a different form of relief than demanded in the complaint is beyond the court’s jurisdiction. (See Marriage of Lippel (1990) 51 Cal.3d 1160, 1167; Electronic Funds Solutions v. Murphy (2005) 134 Cal.App.4th 1161, 1176.) A default judgment for an amount in excess of the prima facie evidence produced at the default hearing is likewise beyond the State Bar’s jurisdiction. (Johnson v. Stanhiser (1999) 72 Cal.App.4th 357, 361-362.)

Without having specified the amount in the Notice of Disciplinary Charges (NDC), the default seeks to impose a civil money judgment through a default, without any claim for damages in the NDC. When recovering damages by a default judgment, the plaintiff is limited to the damages specified in the complaint. In addition, service of a statement of damages in an action not involving personal injury or wrongful death does not satisfy Code Civ. Proc. §580 and the default judgment is void. Sole Energy Co. v. Hodges (2005) 128 Cal.App.4th 199, 206; fn. 4. See also Electronic Funds Solutions v. Murphy, supra, 134 Cal.App.4th at 1176-1177; Levine v. Smith (2006) 145 Cal.App.4th 1131, 1137, citing to the CSC’s decision of Greenup v. Rodman (1986) 42 Cal.3d 822.)

State Bar costs have been determined to be a criminal fine (punishment) and non-dischargeable in bankruptcy. (See Findley v. State Bar of California, 59 Fed.3d 1048 (2010); State Bar Act – §6086.10(e).) Here, the State Bar has found Gottschalk culpable and imposed a criminal and non-dischargeable fine by default in violation of the 6th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution and Cal. Const. Art. 1, §16 right to jury trial. Moreover, the State Bar went to the Legislature to have the “costs” declared to be “punishment” as reflected in the change to the State Bar Act. Now, these “costs” are no longer dischargeable in bankruptcy. (See Penal Code §504 Doe’s disbarment order is unenforceable, because it is void. It has long been held that no court has the authority to validate a void order.

(See U.S. v. Throckmorton, 98 U.S. 61 (1878); Valley v. Northern Fire & Marine Co., 254 U.S. 348, 353-354 (1920). If the underlying order is void, the judgment based on it is also void. (See Austin v. Smith, 312 Fed. 2d 337, 343 (1962).) (See also Armstrong v. Armstrong (1976) 15 Cal.3d 942, 950 [“Collateral attack is proper to contest [a judgment void on its face for] lack of personal or subject matter jurisdiction or the granting of relief which the court has no power to grant [citation omitted].”) (See also Matter of Frazier (Rev.Dept. 1991) 1 Cal. State Bar Ct.Rptr. 676, 697; In re Pyle, 3 Cal. State Bar Ct. Rptr. 929 (1998) [State Bar order or decision subject to collateral attack for want of subject matter jurisdiction or acts in excess of jurisdiction].) (See also, 9 Witkin, Cal. Proc. 5th (2008) Appeal, §45, p.106 [“A judgment that is void on constitutional grounds exceeds the court’s jurisdiction and is subject to attack at any time.” (Emphasis.)]; see also 2 Witkin, Cal. Proc. 5th (2008) Jurisd., § 343, pp. 970-971.)

In California, void orders or judgments issued by the courts are subject to collateral attack in inferior courts, regardless from what court they were issued or affirmed, including the CSC. (See Pioneer Land Co. v. Maddux (1895) 109 Cal. 633, 642-643 [“. . . it matters not whether it was rendered by the highest or the lowest court in the land–it is equally worthless. No one is bound to obey it. The oath of all officers, executive, legislative, or judicial compels them to disregard it.”]; Sullivan v. Gage (1905) 145 Cal. 759, 771; Giometti v. Etienne, 219 Cal. 687 (1934); Hager v. Hager (1962) 199 Cal.App.2d 259, 261.) Moreover, courts are empowered to disregard “law of the case” where it can be demonstrated that it’s based on a void order. (See Moore v. Kaufman, 189 Cal.App.4th 604, 617 (2010); See also, People v. Vasilyan, 174 Cal.App.4th 443, 451 (2009)):

A void judgment may be attacked ” ‘anywhere, directly or collaterally whenever it presents itself, either by parties or strangers. It is simply a nullity, and can be neither a basis nor evidence of any right whatever.’ ” The court concluded that a writ of mandate directing the trial court to “strike the judgment … is the proper remedy.” (Citation.)

Thus, California law recognizes the right to assert a collateral attack, which requires a ruling on the merits – based on the allegations in the Complaints – not summary denials, without a trial. Moreover, numerous cases, including decisions of the CSC, have recognized the jurisdiction of an inferior court to determine a collateral attack of a void order issued from a superior court. (SeeIn re Berry (1968) 68 Cal.2d 137Gonzalez, supra, at 824, the CSC rebukes the COA ruling based on In re Rose. Moreover, “[a] void judgment may be attacked, ‘anywhere, directly or collaterally whenever it presents itself, either by parties or strangers. It is simply a nullity, and can be neither a basis nor evidence of any right whatever.’” (Andrews v. Superior Court (1946) 29 Cal.2d 208

1 See also, Request for Judicial Notice (RJN) Ex.1, 4 J. Legal Advoc. & Prac. 137 [Protecting Those Who Protect Others: The Implications of the Stat Bar Act on Attorneys’ Adjudication Rights in Disciplinary Proceedings; at 154: IV. A Proposed Solution: Transfer to the Courts of Appeal for Mandatory Plenary Review.

2 §6085. Any person complained against shall be given fair, adequate, and reasonable notice and have a fair, adequate, and reasonable opportunity and right:

(a) To defend against the charge by the introduction of evidence.